curated by Rolf Lauter and Marco Vallora

09.12.2006 — 28.02.2007

Toti Scialoja

curated by Rolf Lauter and Marco Vallora

09.12.2006 - 28.02.2007Show introduction

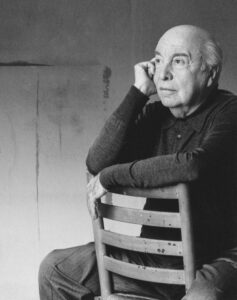

Toti Scialoja, born in 1914 and died in 1998, was one of the protagonists of the long abstract experience in Italy, which since the beginning of the 1950s has remained faithful to the spirit of classical tradition, reserving it a role of absolute centrality against the emphasis of the New York school. The close relationship and the lively and constructive debate established with Afro, Birolli, Melotti, Vedova, as well as the dialogue, behind the apparent spiritual affinities, with the American friends de Kooning and Motherwell, bear witness to this.

The season of “impronte" (footprints) definitively ended in the 1960s, in a phase immediately following the artist’s opening up to compositions marked by rectangular surfaces and inserts defined by clear outlines, absorbing the abstract-geometric impulses peculiar to the time. This was followed by the gradual recovery of a pictorialism that erupts forcefully in the works of the early 1980s, characterized by a peculiar freedom and supported by a more articulated commitment in the literary and poetic fields.

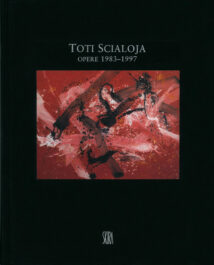

Galleria dello Scudo therefore considered of extreme interest to present, from December 9, 2006, an exhibition of a strictly scientific nature, centered on Scialoja’s abstract research between 1983 and 1997, thus on the last two decades of his artistic career marked by important exhibitions, such as the rich anthology at the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Moderna in Rome in 1991, and by the growth of a stylistic figure based on new compositional rhythms. With a selection of thirty works, the exhibition was held in Verona, from December 9, 2006 to February 24, 2007, realized with the collaboration of Fondazione Toti Scialoja, as part of a project launched in 1999 with the exhibition dedicated to the period included between 1953 and 1966.

The investigation was introduced by a large canvas of 1978, representing the fundamental link between the production of the 1960s and the period for the occasion examined. Here we read the prelude to the next phase: the orthogonal forms, hitherto recurrent in the artist’s works, lost sharpness; the outlines fade, the color became denser, heralding the subsequent recovery of gestures.

The exhibition opened with the paintings Secondo San Isidro and Diario rosso ocra, both from 1983, two of the six vinyl paintings on canvas exhibited the following year in the personal room at the XLI Venice Biennale. The former is inspired by Goya’s La Romería de San Isidro cycle, exhibited at the Prado Museum in Madrid, to which Scialoja looks for the pleasure of representing a long procession dominated by low light tones in majestic compositions. In the second the decisive renewal in the choice of colors is evident: having abandoned the glazes, the artist returns to using earths, now wisely balanced by grays. Vetulonia (1984), is always centered on an accentuated horizontal development, to suggest the idea of an imaginary procession still reminiscent of the canvases of San Isidro. Out of stylistic analogies, it is flanked by contemporary works of a smaller format, such as Agno, Butte and Crimea.

In the summer of 1985 Scialoja was invited to Gibellina, Sicily, to hold a painting workshop. The dazzling light and the open spaces of the place offered the inspiration for a series of paintings – among them Untitled, Gibellina rosso n. 2 and Rug – in which new color ranges emerge for the first time, from light blue to orange, from reds in various shades to bright whites. The brushstroke becomes more dynamic in the rapidity of drafts, now whirling, now broken by sudden intertwining. These paintings were followed by Malavoglia (1985), anticipating works such as Nemo and Marte (1991), marked by an absolute two-tone color. In abandoning balanced chromatic accords, Scialoja faces the close dialogue between black and white. The sign becomes decisive, strengthened by large brushstrokes and sprayed coats that emphasize the contrast between solids and voids.

La Scuola di Atene (1989), the largest canvas ever painted by the Roman artist with its five and a half meters in length, is Scialoja’s masterpiece at the end of the two decades; some sort of challenge, certainly the most demanding due to the obvious problems of construction, and the most audacious due to the desire to relate to the famous fresco painted by Raphael in the Vatican Rooms. A surprising creative happiness supports Scialoja in the paintings of the last period. If with Taraia (1992), made for the XII Rome Quadrennial in which the artist exhibited seven other works, he reached the expressive peak of the new decade, in the coeval Baccanale the characters of the so-called “Ferrara” works emerge, united by colors keeping memory of that ancient school. Already Vermiglio and Tango,(1993), show the tendency to coagulate the gesture in a unitary trend, until it thickens in nuclei being distinct and yet connected to each other, as in La riffa (1995). But it was in 1996 that the artist, then 82, managed to give his painting a further turn of speed: in Contro lo Stemma and Labirinto the gesture explodes violently, dispersing traces of an opaque and deep black onto the surface. In other works of the following year, however, he retains the creative impetus within a clearer structure, as in the large painting that closed the exhibition, Per W.d.K. 20.3.1997, made after the news of de Kooning’s death, together with Motherwell the only one of the past companions with whom Scialoja had kept contact despite the distance.

The exhibition was curated by Rolf Lauter, Director of the Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim, and Marco Vallora, authoritative scholar of Italian informal art. On the occasion, a rich catalog was published by Skira with the scientific contributions of the curators, aimed at highlighting the peculiar traits of Scialoja’s work also in relation to the international context. Paolo Mauri analyzes his poetic commitment, absolutely original due to the singularity of the metric and linguistic experiments, ranging from a taste for nonsense to the creation of hexameters inspired by the Italian tradition. So the texts by Laura Lorenzoni and Barbara Drudi address respectively the critical analysis of the correspondence with contemporary writers, and the biographical story in the years considered by the exhibition, privileging the deepening of the relationships between the author and the protagonists of the overseas art scene. A rich appendix including writings by the artist and unpublished documents completes the book.