Home / Exhibitions / Pietro Consagra, necessità del colore. Sculpture and Paintings 1964-2000

Pietro Consagra, necessità del colore

sculpture and paintings 1964-2000

curated by Luca Massimo Barbero and Gabriella Di Milia

15.12.2007 — 20.04.2008

Pietro Consagra

necessità del colore

curated by Luca Massimo Barbero and Gabriella Di Milia

15.12.2007 - 20.04.2008Show introduction

The thought and the work by Pietro Consagra, born in 1920 and died in 2005, have a very special role in the aesthetic debate of the second half of the twentieth century for the complexity of the themes dealt with, the search for a new relationship between man, space, and sculpture, and for his proposed solutions to a concept of three-dimensionality defined by him as “the monumental matrix of a dead language”. After the large solo exhibitions at the Accademia di Brera, Milan, 1996, the Mathildenhöhe Institut, Darmstadt, the following year, and the Cairo Biennale in 2001, all of which documented, from the ’forties onwards, the multiple “forms” of a certain way of creating art with intelligence and provocation, we believe it was of great interest to present a show taking a new point of view, one that places at the heart of the question certain particular aspects of a long creative career, and underlines just how radical and innovative was the artist’s change of language about halfway through the 1960s.

The stringently methodical show in Verona has been organised with the collaboration of the Archivio Pietro Consagra and was open to the public from December 16, 2007 in both the Galleria dello Scudo and Museo di of Castelvecchio: it was, in fact, in this museum that in 1977 Consagra installed the unforgettable exhibition planned by Giovanni Carandente and Licisco Magagnato. This show of some fifty sculptures and paintings passed in review some forty years’ work, starting from 1964 when the artist’s principle of frontal imagery was extended by his ideas about “double frontality” together with a felicitous use of colour.

From “sculptural necessity” to “colour necessity”: a path the artist was to follow until his last years, beginning with Piani sospesi (1964-1965), and followed by Ferri trasparenti, fantastic bodies with curvilinear outlines and an ever slimmer depth, beautifully represented in the show by Ferro trasparente blu “addio Cimabue” and by Ferro trasparente rosa (1966). There will also be Piani appesi and Giardini, all works exhibited in his solo shows held in 1966 and 1967 in the branches of the Marlborough Gallery in Rome and New York, and in the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam.

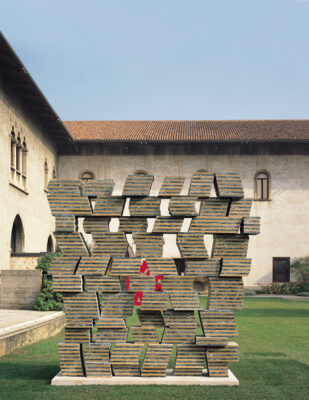

The selection of works in the Castelvecchio museum opened in the superb "Galleria delle Sculture" with Trama, an imposing installation of seven bi-frontal wooden sculptures which have to be considered as one of the most significant examples of Consagra’s new aims. Planned for the 1972 Venice Biennale, it was placed in the entrance to the Italian pavilion in a purposely confined area in order to oblige the viewer to become involved while walking through it.

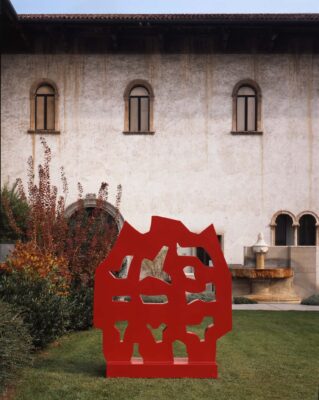

Trama was created in the year when the artist discovered the fascination of “stones” and the infinite polychromatic variations of nature: thus were born sculptures whose strong impact was due to the emphasis on the precious marbles they were carved from and, above all, for a wholly new approach required on the part of the spectator. Examples of this experimentation are to be found both in the Galleria dello Scudo, Bifrontale pietra della Versilia giallo di Siena (1973), and in the Museo di Castelvecchio gardens: two imposing works installed, after careful restoration, where Consagra himself had erected them for the 1977 show, Muraglia “Cangrande”, rosso Magnaboschi and Muraglia, giallo Mori verde Alpi.

Much attention is paid to the artist’s activity as a painter, and this can be seen in various large-scale canvases. The brightly colored Fondo giallo (1981), and the multiplication of images that occupy the whole field of Fondo rosa (1984), underline just how closely involved is their dialogue with the contemporary works in stone or wood: there is almost a short-circuit between them, one that allows Consagra’s painting to be considered as anything but secondary with respect to his sculpture.

Doppia bifrontale closes the exhibition: a white metal piece some five meters long, made in 2000 but later enlarged to even more monumental dimensions for the headquarters of the European parliament in Strasbourg. For its customary and dexterous distribution of fullness and voids, underlined by the purity of a coloring that is almost blatant in its contrast with the architecture of Castelvecchio, this work is the extreme formulation of a highly rigorous aesthetic reflection.

The exhibition was curated by Gabriella Di Milia, art historian and Director of the Archivio Pietro Consagra in Milan, and by Luca Massimo Barbero, Associate Curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, the author of an essay which opens the catalogue, published by Skira, and which traces a stimulating path through the works present in the show. The book also contains a contribution by Fabrizio D’Amico, professor of contemporary art history at Pisa university, which concentrates on the autonomous value of the painting, and a previously unpublished essay by Abraham M. Hammacher, one of the most authoritative specialized critics of the post-war period, who analyses the interests of Consagra with a surprisingly up-to-date interpretation. Photographed by Claudio Abate, the works are divided into four sections and are commented on by Francesco Tedeschi; in the last part Paola Marini, Director of the Castelvecchio museum, presents the essays written in 1977 by Giovanni Carandente and Licisco Magagnato, as the prologue to an in-depth study of the sculptures installed in this prestigious museum. The biographical outline contains numerous previously unpublished documents and is written by Francesca Pola, while Rosemary Ramsey and Lia Durante reconstruct respectively the artist’s critical reception on the other side of the Atlantic and his participation in the Venice Biennale. The catalogue concludes with a research by Laura Lorenzoni who, through an extensive collection of letters, reveals the links between Consagra and his artist friends as well as with critics, art historians, collectors, and the directors of European and American museums.