Home / Exhibitions / Picasso. Dipinti 1918-1968. Acquarelli, disegni, incisioni e litografie 1904-1972

Pablo Picasso Dipinti 1918-1968 Acquarelli, disegni, incisioni e litografie 1904-1972

19.03.1983 — 08.05.1983

Pablo Picasso

Dipinti 1918-1968

Acquarelli, disegni,

incisioni e litografie

1904-1972

19.03.1983 - 08.05.1983Show introduction

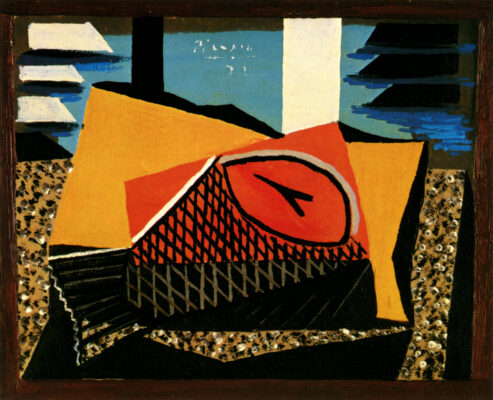

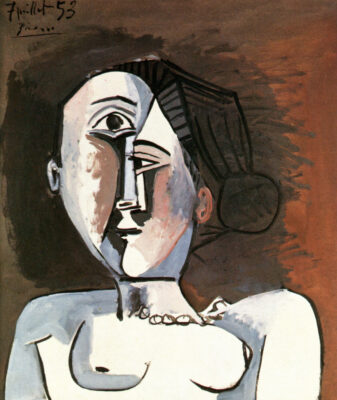

The Pablo Picasso exhibition, held at Galleria dello Scudo from March 19, 1983, gathered a selection of paintings such as Nature morte, verre et journal (1914-1915), Paysage cubiste (1918), canvases of the 1920s such as Morceau de poisson (1922) and Verre taillé (1923), here joined by paintings from the 1940s and 1950s, including Nature morte à la corbeille de fruits (1942), La liseuse, fond noir (1953) and Buste de femme (1953), formerly owned by Curt Valentin, New York. Furthermore, the 1960s are represented by one of the large canvases belonging to Le déjeuner sur l’herbe cycle (1961), hinting at the comparison between Picasso and Manet, and then three works from the series Le peintre et son modèle (1963), up to the great figure of mousquetaire appearing in Homme à la pipe (1968), with all its vibrant colors.

Le repas frugal (1904), an etching opening La Suite des Saltimbanques, world-famous due to the reference to one of the best known subjects belonging to the “Blue Period” (1901-1904), introduces the wide section dedicated to Picasso’s graphic work, proposing some excellent works belonging to the series Le Chef-d’Oeuvre Inconnu (1927), Les Métamorphoses d’Ovide (1930-1931), and La Suite Vollard (1930-1937) commissioned to the artist by the well-known Parisian merchant and inspired by classical mythology.

The two etching and aquatint Sueño y Mentira de Franco, made on January 8, 1937 and gathered in a folder with a prose poem by Picasso on the pain for Guernica, convey the artist’s indignation towards the horror of war. General Francisco Franco is represented as a mad, mythical and monstrous figure, destroying classical Spanish sculpture and, in another detail, fighting a bull that symbolizes Spain.

The exhibition path dedicated to Picasso’s graphic work ends with many lithographs dated between 1940 and 1950, plates from Le Cocu Magnifique (1966) and erotic etchings from Suite 347 (1968).

The catalogue published for the occasion documents the works on display, introduced by a text by Renato Guttuso, of which we publish here the first sentences.

“It has been said that an era closes with the death of Picasso, and we wondered which elements of what belongs to all of us Picasso took with him into his tomb in Vauvenargues. As for the age that is ending, we must find a common interpretation: for some, in fact, the age of Picasso had already been closed with «Guernica»; for others even earlier, in 1916–1917, when he embarked on new paths after having emerged from the golden age of the most rigorous cubism. I think that judgments of this kind are wrong from the start, linked to personal tastes and choices of this or that cultural milieu, and not free from fashionable influences. In the reality of a history less constrained in schemes, less linked to the alternation of taste, Picasso’s work must be understood as a unitary organism, as a vital organ, indeed, in the body of the twentieth century. Since Picasso was never an «experimental» (his is the sentence: ‘I don’t seek, I find’, which is to be understood not as a proud affirmation, but as a declaration of method), paradoxically we can say that from 1905 to the day before his death – since that day he worked until evening – there is neither progress, nor regress in his painting.”