Home / Exhibitions / Giorgio de Chirico, gli anni Venti

Giorgio de Chirico, gli anni Venti

curated by Maurizio Fagiolo dell'Arco

14.12.1986 — 31.01.1987

Giorgio de Chirico, gli anni Venti

curated by

Maurizio Fagiolo dell'Arco

Show introduction

The exhibition de Chirico, gli anni Venti was inaugurated in Verona on December 14, 1986. Organized by Galleria dello Scudo and Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Palazzo Forti and realized under the patronage of Regione del Veneto and Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, it was the first exhibition wholly dedicated to the decade in which the “pictor Optimus”, after the already celebrated season of Metaphysics, renewed his repertoire with subjects destined to further consecrate him in the Parisian and international artistic context.

With a selection of over 70 paintings, some of which have never been exhibited in Europe before, the show proposed an in-depth investigation on the years spent between Rome, Florence and Milan (1920-1925), and then on his stay in Paris, which had a primary importance for the study and maturation of new themes widely developed in his subsequent works.

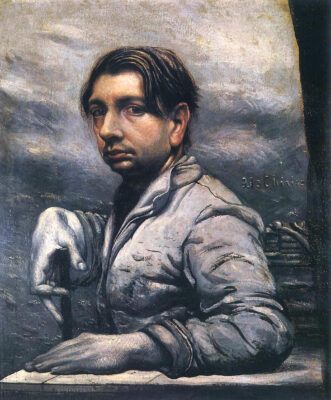

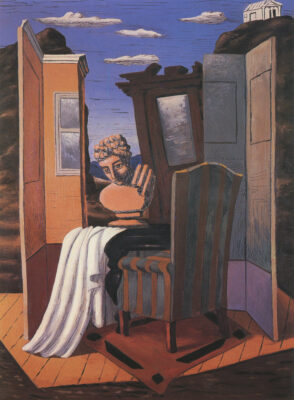

The exhibition was introduced by six self-portraits, including the small canvas (1920) in the Holbein style which belonged to Mario Broglio and then to Alfredo Casella, and the Autoritratto (1924-1925) finally entered Deana collection. Between classical re-enactments and romantic suggestions, the paintings Mercurio e i metafisici (1920) and Edipo e la Sfinge (1920) mark the “enigmatic” side of de Chirico’s painting deriving from the mental overlaps and the cryptic character of the iconographic references. They are joined by Oreste ed Elettra (1923) and La partenza del cavaliere errante (1923), the latter metaphor of the journey of ancient and modern man through unknown regions and countries, seen as physical and mental places. Il condottiero (1925) and Il figliol prodigo (L’enfant prodigue) (1926) are among the masterpieces of the French period. The first entered René Berger’s collection, the second is dominated by the alienating juxtaposition of the phantasmatic character of the son – the statue seen as if in a solarized photo – with the figure of the father, bourgeoisly identified with his red leather armchair.

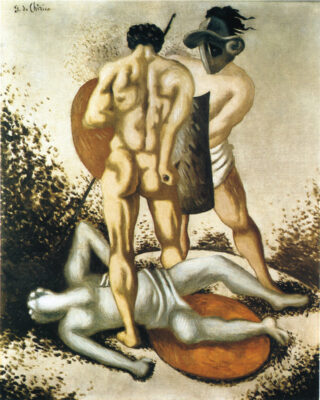

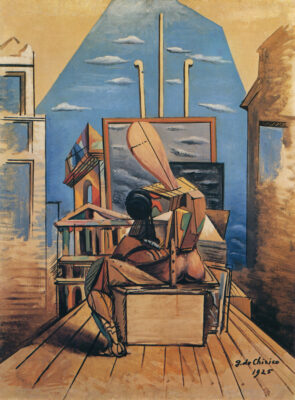

The Parisian period is recalled through a series of canvases, including large-format ones, chosen to document the recurring themes in de Chirico’s painting of the decade, expression of the artist’s double contract with the merchants Léonce Rosenberg (who spread throughout Europe and America with the Galerie de l ‘Effort Moderne) and Paul Guillaume (who was twenty-three at the time of his first meeting with de Chirico and Apollinaire): “Manichini”, “Cavalli in riva al mare”, “Mobili nella valle”, “Figure in un interno”, “I gladiatori”. Among them are Manichino con giocattoli (Les jeux terribles) (1925-1926), chosen for the cover of the Veronese exhibition catalogue, a painting entering the home of Walter P. Chrysler in New York at the end of the 1920s; then Nudo femminile in un interno (L’esprit de domination) (1927), which belonged to Paul Guillaume, unique for its bright, sometimes fluorescent, colours; Combattimento di gladiatori (1927), one of the first paintings in the series executed for Casa Rosenberg, reproduced in the “Bulletin de l’Effort Moderne” (September 1927) and in the monographic volume by Waldemar George (1928).

The exhibition path was closed by a section dedicated to still lifes and to what reprented a prelude to the following decade, such as the large painting Nobili e borghesi (1933), which marked the provisional closure of the Parisian period and the resumption of the invention. Furthermore, documents, photographs, and writings, some of which unpublished, testified to the author’s relationship with both the Italian artistic and cultural context of the time, the surrealists and the Parisian merchants Guillaume and Rosenberg.

The exhibition project was by Massimo Di Carlo with Massimo Simonetti. Divided between the venues of Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Palazzo Forti and Galleria dello Scudo, the exhibition was curated by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco with Massimo Carrà, Giorgio Cortenova and Licisco Magagnato; their contributions, in addition to an intervention by Paolo Baldacci, appear in the rich catalogue published by Mazzotta.