Home / Exhibitions / Boccioni a Venezia

Boccioni a Venezia Dagli anni romani alla mostra d'estate a Ca' Pesaro Momenti della stagione futurista

curated by Ester Coen, Licisco Magagnato and Guido Perocco

01.12.1985 — 31.01.1986

Boccioni a Venezia

Dagli anni romani

alla mostra d'estate

a Ca' Pesaro

Momenti della stagione

futurista

curated by Ester Coen, Licisco Magagnato and Guido Perocco

01.12.1985 - 31.01.1986Show introduction

The exhibition Boccioni a Venezia, organized by Galleria dello Scudo and Museo di Castelvecchio, was held in Verona in the winter of 1985-1986. It analysed the relationships that the leading personality of Italian futurism had with the movement that sees him as its protagonist and with the lively artistic milieu linked to the Venetian exhibitions in Ca’ Pesaro, at the beginning of the 20th century a reference point for new trends inspired by modernism and novelties from beyond the Alps.

The exhibition, organized under the patronage of Regione del Veneto, was divided into two distinct but complementary sections, in a fruitful collaboration between public and private initiatives. The first, “Dagli anni romani alla mostra d’estate a Ca’ Pesaro”, gathered together in Galleria dello Scudo over fifty paintings and a core of drawings, pastels and engravings dated between 1902 and 1910. The second, “Momenti della stagione futurista”, was displayed at Museo di Castelvecchio with paintings from the period 1910–1916.

In the first section, the exhibition route opened with Boccioni’s first experiments in his formative years at the school of Giacomo Balla, attended together with Severini and Sironi: Campagna romana (1903), loaned by Museo Civico di Belle Arti in Lugano, is an exceptional essay of the “new modern technique of ‘divisionism’.” The show continued with the documentation of his travels to Paris and Russia in 1906. During the months spent in Tzaritzin, he painted the great Ritratto di Sophie Popoff, the only known canvas from his Russian stay, remained unknown for a long time and found abroad shortly before the exhibition in Verona. The section then proposed an unprecedented research on the period between Padua and Venice, characterised by pictorial results based on a new conception of light energy and on the use of colour fragmented into a dense texture. Remarkable results of this new phase are Ritratto di scultore and Canal grande a Venezia, both from 1907. The strong bond with his mother, whom he often visited during the year, is testified by some works on paper, including the pastel portrait sent by Musei e Gallerie Pontificie, Città del Vaticano.

Still in 1907 – a year marked by his arrival in Milan, in the “big city” – a new energy manifested itself in a series of paintings exhibited here, such as La Signora Massimino, finished the following year, particularly interesting due to the street view framed within the window, and Autoritratto (1908) from Pinacoteca di Brera, in which Boccioni portrays himself in the foreground, inserting for the first time a hint of Milanese suburbs in the background. The back of this painting, now visible, depicts a self-portrait from 1905–1906 found after a recent restoration.

The last step before Futurism was reconstructed by presenting some of the most significant of the forty-two works exhibited in 1910 at Mostra d’estate in Palazzo Pesaro a Venezia, then introduced in the catalogue by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. It’s the case of Ritratto femminile (1909), the vibrant pastel with the figure in backlight owned by Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, and Mattino and Crepuscolo (both 1909), giving back two visions already revealing the industrial transformation. The leading role is that of Maestra di scena (1910), a painting of “anticipated futurist sign” which, at the time, aroused tepid reactions in the public due to its “pictorial acrobatics”. At the end of the Venetian exhibition, the partnership between Boccioni and Nino Barbantini – Ca’ Pesaro great animator – would come to an end.

The section at Galleria dello Scudo was further enriched by a group of works that highlight Boccioni’s relations with the Italian artists he met between Rome and Paris: Il gorgo (1899–1900) by Duilio Cambellotti, a bronze revealing the predisposition to an antiromantic knowledge of the masses exposed to light; Ritratto della signora Pisani (1901) by Giacomo Balla, a large nineteenth-century canvas in which the opening towards new experiments is already felt; Dintorni di Roma (1903) by Gino Severini, an entirely personal conjugation of the pictorial language of Pointillism; Interno con la madre che cuce (1905 c.) by Mario Sironi, a view rendered with immediate and luminous brushstrokes, emphasising a Segantinian scheme.

The exhibition was closed by the comparison with the figures animating the Veneto milieu, appearing more open to new stimuli from beyond the Alps: among these, Felice Casorati, Tullio Garbari, Arturo Martini and Gino Rossi. Among the relating works were Ritratto della sorella Elvira, painted by Casorati for the Venice Biennale in 1907 and certainly noticed by Boccioni on that occasion; Salice piangente (1907–1909) by Garbari, an example of the complexity of the stimuli deriving from a Mitteleuropean formation; Ritratto di pescatore con paesaggio (1909 c.) by Gino Rossi, then still unknown, and La prostituta (1909–1913) by Arturo Martini, coming from the Venetian public collections – both overwhelmingly expressive works that are affected, respectively, by the strong chromatic intensity of Fauve and the influences of African art, then fashionable in Paris.

Furthermore, a rich documentary apparatus, consisting of photographs, letters and writings, some of which unpublished, offered an interesting corollary to deepen some aspects of the examined historical-artistic context.

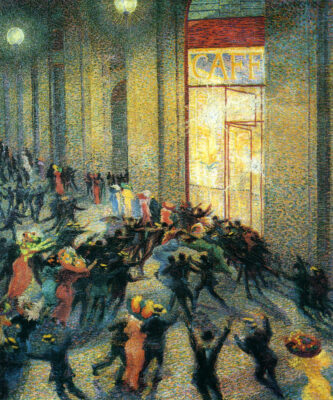

The second section of the exhibition, set up at Museo di Castelvecchio, included a selection of Futurist paintings from public and private collections carried out between 1910 and 1914, to testify the further results of Boccioni’s language. Three of them came from Pinacoteca di Brera: Rissa in Galleria (1910) formerly Jesi donation; Elasticità (1912) and Il bevitore (1914) both part of the Jucker deposit. If the first painting reveals the artist’s attempt to develop an energetic tension with a still pointillist technique, the other two confirm the definitive transition to the study on the interpenetration of planes with a completely original expressive freedom. The plastic interest in the figure is dominant in Antigrazioso (1912), a portrait related to Picasso’s primitivism and belonging to Margherita Sarfatti. Equally important is the provenance of Forme plastiche di un cavallo (1913–1914), the small canvas that Giuseppe Sprovieri kept for himself after the exhibitions in his galleries in Rome and Naples.

The section was further enriched by three works on loan from CIMAC - Civico Museo d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan, gifted by Ausonio Canavese: Dinamismo di un corpo umano (1913) boasting violent colours where form and light take on an absolute value; Sotto la pergola a Napoli (1914) and the concise Dinamismo di una testa d’uomo (1914), to be framed within the phase in which Boccioni reached the solidification of the image through volumes. If Cavallo + Cavaliere + Caseggiato (1913-1914), from Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, heralds the return to a post-impressionistic luminosity in an analysis that will lead to the direct meditation on Cézanne, Ritratto della signora Busoni (1916) marks the turning point in this direction, the last possible experimentation before death.

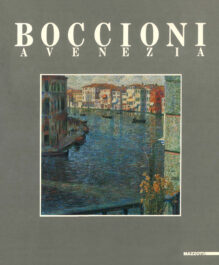

The catalogue, published on the occasion by Mazzotta, includes essays by the curators of the exhibition: Ester Coen, co-author in 1983 of Boccioni general catalogue; Licisco Magagnato, director of Musei Civici, Verona; Guido Perocco, former director of Musei Civici, Venice. Further contributions in the book are by Marco Rosci and Walter Schönenberger, director of Museo Civico di Belle Arti in Lugano.