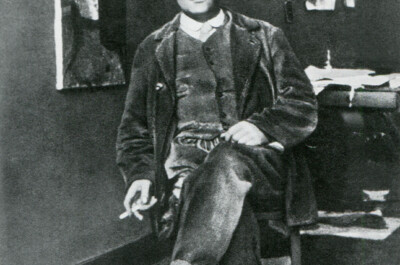

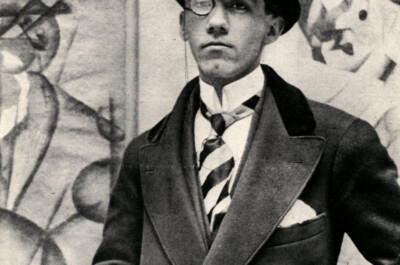

Umberto Boccioni was born in Reggio Calabria in 1882; his parents were from the Romagna region. As a result of continual changes of home (his father was employed by the prefecture), he went to school in Reggio Calabria and then Forlì, Genoa, Padua, and finally Catania where he gained a diploma from the technical college. He already showed a great interest in literature and, despite his low marks, in drawing too.

In 1899, after arguments with his family, he went to live with an aunt in Rome and enrolled for a course of life drawing, at the same time studying drawing with the poster designer Matalani, because the thought the academy was too antiquated and repressive. He became friends with Gino Severini, and Giacomo Balla who, just returned from Paris, had a decisive influence on both them and other artists who frequented his studio at Porta Pinciana. He came into contact with Divisionism and gained a knowledge of contemporary French painting; he was also interested in the Symbolism of Sartorio, De Carolis, Pellizza da Volpedo, Meunier, and Klimt. Umberto Boccioni became interested in the cultural, artistic, and philosophical situation in Europe, and developed his own convictions through reading Sorel, Nietzsche, and Renan. He also wrote an unpublished novel (Pane dell’anima, 1900) and collaborated with some periodicals. In particular, together with Severini, he studied landscape and painted in the open air in the Roman countryside, taking particular notice of the atmosphere’s luminous effects.

In 1901 he made his first known drawing for the birthday of his sister Amelia, and another, a Figura maschile. In 1904 he exhibited Paesaggio at the annual show of the Amatori e Cultori, Rome, and in the following year he was to be seen again with Autoritratto. He won a painting competition and, from April 1906, Umberto Boccioni spent five months in Paris, where he studied the painting of the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists – Cézanne in particular –, investigated in depth the relationship between man and nature, and studied a more marked scansion of the planes. He then went to Russia (Tzarin, Egoritzin, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg) and, on his way back home, stopped off at Warsaw and Vienna.

On his return to Italy in December 1906, he stayed with his family in Padua where he spent a period reflecting on the experiences he had been exposed to, and also showed, as can be read in his diary, great intolerance for the limited horizons of international art, which could be seen in the Venice Biennale of that year. “I want to paint again, the result of our industrial times”, he stated in his diary; in the meantime he made use of a Divisionism in which a free and spontaneous creativity prevailed over technical minutia. He moved to Venice where, in April 1907, he enrolled with the academy of art, but after just a few months, in August he moved back to his mother and sister who had, in the meantime, moved to Milan, where he too settled. After being disoriented by the spread of Art Nouveau and the Secession art seen in Austria, as well as the doubts he had undergone while in Padua, he found Milan to be a constructive city full of ideas, anarchic tensions, a search for progress, and socialist ideologies.

On 2 March 1908 he met Previati whose Tecnica della Pittura he had already read. We have now reached the second period of the Divisionism of the pre-Futurist Boccioni, when he made use of an aerodynamic touch incorporating a light similar to that of Previati; at the same time he was attentive to psychological aspects, states of mind, reality, and the industrial society. In fact, in his portraits there were to be seen workshops and city landscapes in the process of change and full of life (Ritratto della madre, 1907; Autoritratto, 1908; Officine a Porta Romana, 1908), and an emphasising of swirling light (Controluce, 1909-1910). In his graphic work of the same time he was influenced by the lines of Munch, Klimt, Durer, Beardsley and also by the illustrations by Previati for Poe’s tales. Again in 1908 he exhibited his pastel Interno at the Espozione Nazionale di Belle Arti in Milan.

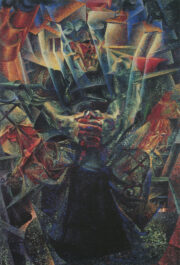

Umberto Boccioni had a meeting in 1909 with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti which was to prove fundamental for his development. In that very year Marinetti had published, in the 20 February issue of “Figaro”, his Manifesto del Futurismo and, on 10 February 2010, together with Russolo, Carrà, Balla and Severini, Boccioni signed the Manifesto dei pittori futuristi which, in a rejection of the past, glorified the myths of modern progress. This was followed on 11 April by the Manifesto tecnico della pittura futurista. This, by pinpointing “movement” as the basis of life, for which things and figures amalgamated, and the viewers themselves were virtually placed at the heart of the painting, reflected the fundamental ideas of “dynamism” and “simultaneity” in a personal interpretation of Bergson’s vitalistic concept of duration. In fact for Boccioni, and differently from Balla and Russolo, the time dimension was not considered to be a succession of moments, nor was movement considered as the optical principle of retinal persistence. It was considered as an overall aspect of consciousness (“duration”) in which memories of actions from the recent or distant past are perceived simultaneously; what was of interest was the reason for the action. From this period dated Il lutto, 1910 (two old women, one with white hair, the other with red, are portrayed simultaneously in three attitudes of tragic pain), and La città sale (1910-1911) (a single and symbolic upward swirl that involves a horse, a man, and buildings under construction, all repeated from different views). In July 1910 Marinetti presented a group of forty-two paintings by Boccioni at the “Mostra d’estate” in Ca’ Pesaro, Venice.

In 1911 he discovered Cubist painting and, in 1912, Cubist sculpture, and was influenced by both. On 11 April 1912 he published the Manifesto della scultura futurista in which, as a result of the idea of abolishing “finished” lines and “closed” statues, the objects, atmospheric planes, and the environment around things are all joined together. Consider, for example, the paintings Sviluppo di una bottiglia nello spazio (1911); Antigrazioso (La Madre) (1911). In 1913 he made a series of sculptures which in an increasingly strong manner synthesised the interaction between space, matter, and movement (Forme uniche nella continuità dello spazio and Sviluppo di una bottiglia nello spazio).

In March 1914 he published his book Pittura Scultura Futuriste (Dinamismo plastico) and the unpublished Manifesto dell’Architettura Futurista. He took part in all the Futurist exhibitions in Italy and abroad until 1914. In 1915, on Italy’s declaration of war, together with his Futurist friends he enlisted in the Voluntary Battalion of Cyclists and left for the front. The experience of war led him to isolate himself and rethink his ideas. In his painting the dynamic element increasingly gave way to a Cézanne-like plasticity (Ritratto del Maestro Busoni). After a furlough spent in Milan (from December 1915 to July 1916), Umberto Boccioni was recalled for an artillery regimental campaign and went to Sorte, near to Verona, where shortly after he died.