Rossi, Gino was born in Venice in 1884 to a wealthy family (his father was the administrator for Count Bardi whose famous collection of exotic objects was to be conserved in the Museo Orientale in Venice). However, almost nothing is known about the period between leaving the Foscarini school in 1898 and his journey to Paris with Arturo Martini in 1906-1907. It is known that in 1903 he married the painter Bice Levi Minzi, that later he was trained privately by the Russian painter Schereschevsky, and that already in 1905 he had a studio in Palazzo Pesaro.

In Paris he studied with the then famous Spanish artist Anglada, but he knew he had to go further and so he frequented Medardo Rosso, looked at Cézanne and at Art Nouveau (even though without visiting Munich or Vienna) and, above all, at Matisse, the Fauves, and such Nabis artists as Sérousier, Lacombe, Denis, and Bernard; he then went back to the immediate sources of their chromatic freedom: Van Gogh and, even more, Gauguin who was to become his main reference point. His studies of Medieval and Flemish art (first in Parisian museums and then more thoroughly on a journey to The Netherlands), as well as of the Oriental ceramics in the Cluny Museum and of Byzantine mosaics, hint at the beginnings of a Nabis sensibility, one that united ethics and aesthetics in an almost mystical conception of art, something he was able to fully develop during a second journey to Brittany at the end of 1909 following in the footsteps of Gauguin. In the meantime Gino Rossi had taken part in the first show at Ca’ Pesaro in 1908 and in the third in 1909, where he began a lifelong friendship with Barbantini.

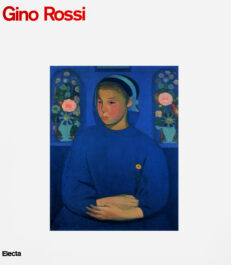

It was in 1910 that, having settled in Burano (an island that until 1915 was to be “his own” Brittany and that of his Ca’ Pesaro friends Moggioli, Scopinich, and Semeghini), the artist established his reputation at Ca’ Pesaro with La fanciulla del fiore, Il muto, and Case a Burano (in the following year he was also to hold a solo show at Ca’ Pesaro). For some years he was to paint with flat applications of pure, anti-naturalistic, and enamelled colour (with a prevalence of greens and blues), now enclosed in Gauguin-like cloisonnées lines (La fanciulla del fiore, Paese in Bretagna; and also Douarnenez in the Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Venice), with the occasional concession to the sinuous decorative lines of Matisse (Primavera in Bretagna, in the Museo Civico, Treviso; Mestizia, Tina, Maria e Fina, Composizione con figure, and Tre donne danzanti), and at times with the outlines of a tortuous expressionism inherited from Van Gogh and that defined the figures of the rough fishermen from Brittany or Burano in some portraits, mostly dating from 1912-1913 (besides the aforementioned Muto, Il vecchio pescatore in the Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan, and Pescatore dal berretto verde, L'uomo dal canarino, Il bevitore). During the Burano years, Gino Rossi often went to Asolo which was to inspire landscapes so free in the relationships between marks and colours as at times to almost approach abstraction (as in Grande descrizione asolana, 1912).

In 1912 the artist went once again to Brittany and to Paris with Arturo Martini in order to take part in the Salon d’Automne. Here the attention he paid to the sculpture of Archipenko, and above all his rethinking about Cézanne – deepened further in a third journey to Paris in 1914 – led him to slowly abandon his earlier decorative elegance and brilliant colour in favour of something “more harsh, more tough” – in his own words – in his search for a “plastic awareness” that could utilise colour for the constructive functions of form. Furthermore, shortly after the 1912 trip, his wife left him and the following trauma was to mark him forever, veiling his next works with an incurable melancholy. At the Ca’ Pesaro show in 1913, his sombre landscapes and, above all, the severe composure of Maternità (Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Venice), by then revealed the turning point that was to be exploited in the following year in such masterpieces with austere colours and tight architectural structures as L’educanda and Ritratto di signora. In 1914 Rossi exhibited at the Venice Lido together with the “artists rejected by the Biennale”, in Rome in the Secession exhibition (as in the previous year), and the Futurist show held by the Galleria Sprovieri.

In 1915 he moved from Burano to Ciano sul Montello. For him the war meant imprisonment in Restatt, Germany, which was to permanently undermine his health and spirits. On his return (the house in Ciano had been destroyed and many of his works lost) he settled with his mother in Noventa Padovana until 1922, and then once again in Ciano. His psychological discomfort was increased by his poverty which forced him to work as a ceramicist and as a travelling salesman, but this did not stop him from once more taking up painting, the artistic battles with his friends from Ca’ Pesaro, and his exhibition activity.

In 1919 he was to be seen at the Ca’ Pesaro show and at that of the “Soldati Congedati” in Verona, as well as at, on the invitation of Casorati, the Promotrice in Turin; in 1920, once again turned down by the Biennale, he was together with the Ca’ Pesaro dissidents at the Galleria Geri Boralevi in Venice and, in 1921, at the II Esposizione Nazionale d’Arte in Padua and the Regionale in Treviso, as well as at the Galleria Pesaro in Milan. In 1924 he exhibited at the Mostra Trevigiana d’Arte at Palazzo Provera, once again at Ca’ Pesaro and, in 1925, in the new venue of the Bevilacqua La Masa on the Lido.

His final works, after the pause during the war, followed a decidedly Cézanne-Cubist path, which was given a further boost by his last journey to Paris in 1919, and that was expressed through minimal and rigorous volumes – his “picture architecture” – both in his figure paintings (from Testa di ragazza, 1920, to Fanciulla che legge, 1922, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Modern, Rome; and to the Composizioni – which are imposing even though on a small scale - made in his final period of lucidity), in his landscapes (Tramonto a Burano, Colline, Case in collina) and, even more so, in his series of still-lifes from 1922-1923, which he defined as “constructions”, and which were the most in line with his belief that “you do not construct with colour, you construct with form”. In 1926 Rossi became insane and for the remaining twenty years he survived in various mental institutions. Gino Rossi died in that in Treviso on 16 December 1947.