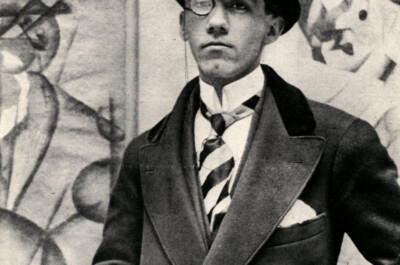

Felice Casorati was the great protagonist of painting in Piedmont in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Novara in 1883 - where his father, a professional solder, was stationed at the time – into a family from Pavia that was well-known for its mathematicians, lawyers, and doctors. After stops at Milan, Reggio Emilia, and Sassari, during the family’s period in Padua the young Felice had a serious nervous breakdown and was forced to interrupt his studies as a pianist, which was intended to be his career, and he began to paint. Rather than interrupting his art, his graduation in law (1906) intensified it.

This period was to be crowned by his participation in the 1906 Venice Biennale with an elegant Ritratto di signora, which was favourably noted by the critics. In 1908 he and his family moved to Naples where he began an ambitious series of figure paintings in which there were conjoined an aristocratic antique patina, echoes of Breughel, and the style of Ignacio Zuloaga, an artist he deeply admired: all this was to be seen in the works he sent to the Venice Biennale in 1909 (Le figlie dell’attrice, Le vecchie) and in 1910 (Le ereditiere). The two solo shows held by Gustav Klimt in Venice in 1910, and in Rome in 1911, greatly influenced his production in the second decade. He made use of Secessionist styles, brilliant colouring, and elegantly decorative methods. His family moved to Verona in 1911, and this allowed him to become part of the young group of artists based around Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, and it was here that in 1913 he exhibited in a room devoted only to his work, and where he was to return in 1919.

Although he was a protagonist of a spiritualist avant-garde, with the brilliant colours typical of Symbolism and a strong graphic personality (testified to by his presence in the Rome Secession where, in 1915, he was again to have a room to himself), he did not break off his relationships with the more official Venice Biennale where, in 1912, he had a personal success with the sale of two paintings to the Ca’ Pesaro gallery and to the Belgian government.

After the war Felice Casorati's activity was to be particularly significant in catalysing his youthful energies (shows in Verona in 1918; Turin 1919; exhibition of the Ca’ Pesaro dissident artists, 1920; the Turin Quadriennale show, 1923). But it was to be his painting above all that became fundamental for the “return to order” of Italian painting.

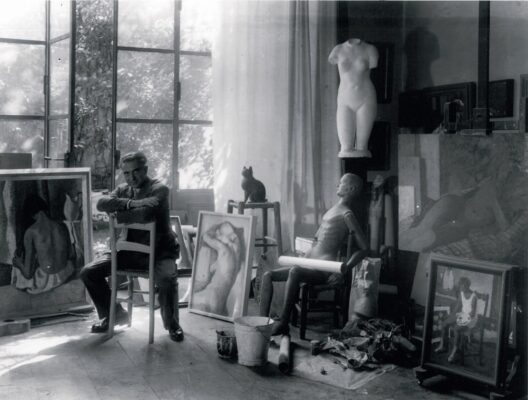

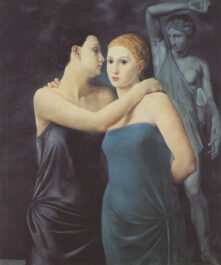

The recovery is initially characterized by a phase of reconstruction of a space that is only apparently rigorous, of a metaphysical enigmatic nature (L'attesa, 1918-19; Anna Maria De Lisi, 1919; Mattino, 1920; L'uomo delle botti, 1920). Then, on the wave of the impression aroused by Cezanne's exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1920, the painter attempted to solidify his painting in a neo-fifteenth-century and classicist direction in large compositions of figures set in his studio and portraits of silent and puristic solemnity, works presented at the most important exhibitions of the 1920s and destined to arouse one of the most heated debates in Italy on the modern; in particular, the personal room at the Venice Biennale in 1924, presented by Lionello Venturi and set up at the same time as that of Ubaldo Oppi and that of the painters of the Italian twentieth century, will confront visitors for the first time with the problem of the intellectualistic return to antiquity and the definitive break with the ties of nineteenth-century painting.

The painter's sales success was constant, with a prestigious private clientele (Gualino, Casella, Ojetti, Pecci Blunt, Sarfatti) and public institutions (all the main Italian galleries and many foreign ones, including the Museums of Boston, Pittsburgh, Budapest, the Luxembourg in Paris, the Nationalgalerie in Berlin) and with almost unanimous critical acknowledgment, if we exclude voices closely linked to 19th-century conservation.

In about 1920-30, he accepted invitations to the Venice Biennale and the first Quadriennale in Rome, Felice Casorati’s painting, after a brief period of interest in landscape, decisively changed and saw a rejection of the chilly neo-Mantegna purity of the recent past in favour of a painting that, with its mainly tenuous and pearly hues, tended to open up and amalgamate (Susanna, 1929; La toeletta, Conversazione alla finestra, Tre sorelle, 1930) inspired by the contemporary work of the Sei Pittori group in Turin.

After the Second World War (in 1941 the painter had been appointed professor of Painting at the Albertina Academy in Turin) Felice Casorati's activity continued for almost twenty years until his death, with works, mostly figures and still lifes, with a very clear spatial score and a decorativeness not immune from the contemporary fortunes of Abstractionism.

Lastly, FeliceCasorati's multifaceted non-pictorial activity deserves to be mentioned: in the first place that of engraving, particularly dense in the second decade of the century; then the sculptural one (polychrome heads at the Roman Secessions, friezes and statues for the Gualino theater, the relief for the Macelleria at the 1925 Monza Biennale, a relief at the 1933 Triennale); the mosaic one (two large mosaics for the Brussels Exhibition of 1934 and for the VI Triennale of Milan in 1936); that, very notable, of theatrical set and costume designer at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino (1933, 1935, 1950), at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan (1942, 1946-50), at the Venice Festival (1947), at the Eliseo in Rome (1950), at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan (1951).